Mikoyan's "Mission Impossible" in Cuba:

New Soviet Evidence on the Cuban

Missile Crisis

The Soviet Cuban Missile Crisis:

Castro, Mikoyan, Kennedy, Khrushchev, and the Missiles of November

By Sergo Mikoyan, Ed. Svetlana Savranskaya

Mikoyan Archive Reveals Cuba a Near-Nuclear Power

New Book Shows Crisis Unresolved Until November 22, 1962

Posted - October 10, 2012

Edited by Svetlana Savranskaya

For more information contact:

Svetlana Savranskaya - 202/994-7000 or nsarchiv@gwu.edu

Anastas Mikoyan discovers Cuba, February 1960. Photo courtesy of Sergo Mikoyan.

Purchase The Soviet Cuban Missile Crisis: Castro, Mikoyan, Kennedy, Khrushchev, and the Missiles of November at Amazon.

RELATED LINKS

Cuba Almost Became a Nuclear Power in 1962

By Svetlana Savranskaya, Foreign Policy, October 10, 2012

RELATED POSTINGS

The 40th Anniversary Cuban Missile Crisis Conference in Havana

One Minute To Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War

By Michael Dobbs, June 4, 2008

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Mikoyan and Castro, a difficult handshake. Photo courtesy of Sergo Mikoyan.

Mikoyan and Castro negotiating. Photo courtesy of Sergo Mikoyan.

Mikoyan and Castro. Photo courtesy of Sergo Mikoyan.

Washington, DC, October 10, 2012 – In November 1962, Cuba was preparing to become the first nuclear power in Latin America—at the time when the Kennedy administration thought that the Cuban Missile Crisis was long resolved and the Soviet missiles were out. However, the Soviet and the Cuban leadership knew that the most dangerous weapons of the crisis—tactical Lunas and FKRs—were still in Cuba. They were battlefield weapons, which would have been used against the U.S. landing forces if the EXCOMM had decided on an invasion, not the quarantine. The Soviets intended for them to stay in Cuba secretly because they were not part of the Kennedy-Khrushchev understandings, while the Cubans wanted to keep them to defend against another U.S. invasion. But Soviet Deputy Prime Minister Anastas Mikoyan brought the final resolution to the Cuban Missile crisis on November 22, 1962 in his four-hour conversation with the top Cuban leadership: the tactical nuclear weapons would have to leave Cuba.

These revelations come from documents donated to the National Security Archive by our long-time partner, historian and personal secretary of his father, the late Sergo A. Mikoyan. The documents are being published for the first time in English in the book by Sergo Mikoyan, edited by Svetlana Savranskaya, The Soviet Cuban Missile Crisis: Castro, Mikoyan, Kennedy, Khrushchev and the Missiles of November (Stanford University Press/Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2012). The documents published here today are the first part of the publication of the donated "Mikoyan archive" by the National Security Archive.

The new Soviet documents show that Khrushchev decided to place the missiles in Cuba because he was under the impression that a US invasion was just a question of time, and he was not willing to lose his new Cuban ally, which constituted a forward base of socialism in the Western hemisphere. He felt humiliated by the US missiles in Turkey virtually on the border of the USSR. He was also concerned by the enormous gap between the US and Soviet deliverable nuclear firepower. Fidel Castro objected to a deployment that would have made him look like a Soviet puppet, but was persuaded that missiles in Cuba would be in the interests of the entire socialist camp. The unprecedented secret deployment followed, but was not completed. The Kennedy speech on October 22 brought the crisis into the open. Khrushchev's conciliatory letter of October 28 let the world breathe the sigh of relief. Yet, the crisis was far from resolved.

With 42,000 combat personnel, 80 nuclear armed front cruise missiles (FKRs), 12 nuclear warheads for dual-use Luna launchers, and 6 nuclear bombs for IL-28s still in Cuba and not covered in the exchange of letters between Kennedy and Khrushchev, the Soviet leader knew he had a problem. Castro, who was not consulted or even informed of the deal, was angered by the Soviet betrayal and refused to allow any inspections of the Soviet withdrawal. The Soviets had to take back the missiles, get the US to confirm its non-invasion pledge, and—most importantly—keep Cuba as an ally. Only in this way could the Soviets resolve their own Cuban crisis. There was only one person who could negotiate this resolution—Deputy Prime Minister Anastas Mikoyan.

Mikoyan arrived in Cuba in early November 1962. Already in the first conversations with the Cuban leaders, he felt their "acute dissatisfaction with our policy." The Cubans felt humiliated and betrayed by their ally. While they were prepared to fight a nuclear war and "die beautifully," in the name of the socialist camp, the Soviets were negotiating with the imperialists behind their backs. Mikoyan tried to explain to the Cubans why they were not apprised of the Soviet decision to withdraw the weapons. He cited the lack of time and the fear of an American invasion amplified by the letter from Castro of October 27. Mikoyan assured the Cubans: "you know that not only in these letters but today also, we hold to the position that you will keep all the weapons and all the military specialists with the exception of the "offensive" weapons and associated service personnel, which were promised to be withdrawn in Khrushchev's letter." While Mikoyan tried to get Castro to accept some form of inspection in Cuba, the Cuban leader shocked him by not only flatly refusing any inspections but saying emotionally that if the Soviets thought the Cuban position was unreasonable, then "we would think it more correct to consider the Soviet side free of its obligations and we will resist by ourselves. Come what may. We have the right to defend our dignity ourselves." Did the Cubans just say that they did not need such unreliable allies and that the Soviets could now simply go home? [Document 1, Telegram from Mikoyan to the CC CPSU. November 6, 1962]

No sooner had Mikoyan succeeded (barely) in bringing the Cubans back from the brink—by showing respect and empathy and promising that not a single additional concession would be made—the Soviet leadership in Moscow decided that they had to agree to a new US demand—to withdraw the IL-28 nuclear capable bombers. Khrushchev sent a long and rambling cable to Mikoyan giving him arguments to use with the Cubans regarding the new concession. He started by asking for Mikoyan's opinion, "since by now you are almost like a Cuban." Khrushchev reaffirmed the Soviet position that the rest of the weapons would stay in Cuba and be transferred to the Cubans gradually: "after the removal of the missiles and Il-28s, there would be no weapons that the Cubans could not master on their own. […] [T]he weapons that were shipped to Cuba are already there and nobody is thinking of removing them. Later, when the situation is normalized, most likely it would be expedient to transfer those weapons to the Cubans." He asked Mikoyan to give the Cubans assurances of lasting Soviet friendship and support, and to try to persuade them that giving up the ILs would actually be in the Cuban interest because then the Soviet Union would be able to extract from the Americans a formal non-invasion pledge. The Cubans had good grounds to be skeptical about that promise. [Document 2, Telegram from Khrushchev to Mikoyan. November 11, 1962]

Castro accepted the concession, but refused to see Mikoyan for two days and in the meantime ordered Cuban forces to shoot at low-flying U.S. reconnaissance planes, bringing on another crisis within the crisis. In trying to get Castro to accept the withdrawal of the bombers, Mikoyan once again gave assurances that no further concessions would be made and that the rest of the weapons would stay in Cuba. But in the course of daily conversations with the Cuban leadership, he began to appreciate the danger tactical nuclear weapons would pose if they were left on the island, especially in Cuban hands. If the Americans learned about their presence in Cuba, the situation could quickly spiral out of control. And in the future Cuba was not providing assurance that it would be a cooperative ally as far as foreign policy was concerned.

The final straw came on November 20 when Castro sent instructions to Cuba's representative at the United Nations, Carlos Lechuga, to use references to the tactical nuclear weapons that Cuba had as leverage in negotiations, and also as a way to establish the fact that the weapons were in Cuban possession. Mikoyan became extremely worried about that message and suggested to the Soviet Party Presidium that when he next spoke with Castro about the military agreement between Moscow and Havana, he should inform the Cuban leader that all tactical nuclear weapons would be withdrawn from Cuba. In doing so, he was well aware of the sensitivity of the issue for the Cubans and of their likely reaction to the prospect of the Soviets removing this last means of resistance to US aggression. Mikoyan knew that he had to break this unpleasant news to his hosts, and he had to do it in a way that would ensure they remained Soviet allies.

In the most crucial moment of his mission, Anastas Mikoyan and the Cuban leadership had a four-hour conversation on November 22, in which he informed them of the latest decision to withdraw all tactical nuclear weapons. That was the final blow to the Cuban revolutionaries, after they had, in their eyes, been made to suffer so much. Castro opened the conversation by saying that he was in a bad mood because Kennedy had stated in his speech that all nuclear weapons had been removed from Cuba. Castro's understanding was that the tacticals were still on the island. Mikoyan confirmed this and assured him that "the Soviet government has not given any promises regarding the removal of the tactical nuclear weapons. The Americans do not even have any information that they are in Cuba." The Soviet government itself, said Mikoyan, not as a result of US pressure, had decided to take them back. [Document 3, Memorandum of Mikoyan's Conversation with Castro, Dorticos, Guevara, Aragonez and Rodriguez. November 22, 1962]

The IL-28 bombers came up again. Mikoyan tried to persuade Castro that "as far as Il-28s are concerned, you know yourself that they are outdated. Presently, it is best to use them as a target plane." To this, Castro retorted: "And why did you send them to us?"

During their discussions, Castro was very emotional and at times rough with Mikoyan—criticizing the Soviet military for failing to camouflage the missiles, for not using their anti-aircraft launchers to shoot down US U-2 spy planes, essentially allowing them to photograph the missile sites. He went back to the initial offer of missiles and stated that the Cubans did not want the missiles, but that they accepted them as part of "fulfilling their duty to the socialist camp." They were ready to die in a nuclear war, he declared, and were hoping that the Soviet Union would be also willing "to do the same for us." But the Soviets had not treated the Cubans as a partner, Castro complained. They had caved in under US pressure, and had not even consulted the Cubans about the withdrawal. Castro expressed the humiliation the Cubans felt: "What do you think we are? A zero on the left, a dirty rag. We tried to help the Soviet Union to get out of a difficult situation."

In desperation, Castro almost begged Mikoyan to leave the tactical warheads in Cuba, especially because the Americans were not aware of them and they were not part of the agreement between Kennedy and Khrushchev. Castro claimed that the situation now was even worse than it had been before the crisis—Cuba was defenseless, and the US non-invasion assurances did not mean much for the Cubans. He was concerned that the Soviets were withdrawing all their forces from Cuba. But Mikoyan was now convinced that leaving any nuclear weapons in Cuba would be reckless and dangerous, so he rejected Castro's pleas and cited a (nonexistent) Soviet law proscribing the transfer of nuclear weapons to third countries. Castro had a suggestion: "So you have a law that prohibits transfer of tactical nuclear weapons to other countries? It's a pity. And when are you going to repeal that law?" Mikoyan was non-committal: "We will see. It is our right [to do so]."

This ended Cuba's hope of becoming a Latin American nuclear superpower.

Ironically, if the Cubans had been a little more pliant, and a little less independent, if they had been more willing to be Soviet pawns, they would have kept the tactical nuclear weapons on the island. But they showed themselves to be much more than just a parking lot for the Soviet missiles. They were a major independent variable of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Mikoyan treated his Cuban hosts with great empathy and respect, while being highly critical of his own political and military leadership. He admired the genuine character of the Cuban revolution; he saw its appeal for Latin America. But he also saw the danger of the situation spinning out control probably better than other leaders in this tense triangle. As the new evidence in this book makes clear, Anastas Mikoyan should be credited with the final resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 400

Posted - October 27, 2012

Edited by Svetlana Savranskaya, Anna Melyakova and Amanda Conrad

Pentagon Estimated 18,500 U.S. Casualties in Cuba Invasion 1962, But If Nukes Launched, "Heavy Losses" Expected

Gen. Taylor Proposed Major Retaliation if Cubans "Foolhardy" Enough to Try to Repel U.S. Invasion with Nuclear Weapons

But Taylor Warned There Would Be "No Experience Factor Upon Which to Base an Estimate of Casualties"

Pentagon Accountants Estimated Missile Crisis Cost $165 Million Dollars, Over $1.4 Billion in Current Dollars

National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 397

Posted - October 16, 2012

Edited by William Burr

For more information contact:

William Burr - 202/994-7000 or nsarchiv@gwu.edu

Washington, DC, October 24, 2012 – Extreme temperatures, equipment breakdowns, and the reckless deployment of nuclear torpedoes aboard Soviet submarines near the quarantine line during the Cuban Missile Crisis 50 years ago this week elevated the already-high danger factor in the Crisis, according to Soviet and American documents and testimonies included in a new Web posting by the National Security Archive (www.nsarchive.org).

The underwater Cuban Missile Crisis received new attention this week with two PBS Television shows, one of which re-enacts as "overheated" docudrama (in the words of The New York Times reviewer) the confrontation between U.S. Navy sub-chasing units and the Soviet submarine B-59, commanded by Valentin Savitsky, on the most dangerous day of the Crisis, October 27, 1962.

The newly published documents in the posting include the original Soviet Navy map of the Caribbean showing the locations of the four "Foxtrot" diesel submarines that had deployed from the Kola peninsula northwest of Murmansk on October 1, 1962, bound for Mariel port in Cuba to establish a submarine base there. Unknown to the U.S. Navy, each of the subs carried a nuclear-tipped torpedo, with oral instructions to the captains to use them if attacked by the Americans and hulled either above or below the waterline.

The documents include the never-before-published after-action report prepared by Soviet Northern Fleet Headquarters after the four commanders' return to Murmansk in November 1962, describing the atrocious conditions aboard the subs, which were not designed for operations in tropical waters.

The posting also includes the U.S. Navy message on October 24, 1962, detailing the "Submarine Surfacing and Identification Procedures" to be followed by U.S. forces enforcing the quarantine of Cuba, including dropping "four or five harmless explosive sound signals" after which "Submerged submarines, on hearing this signal, should surface on Easterly course." The State Department communicated this procedure to "other Governments" including the Soviet Foreign Ministry, but the Soviet submarine commanders, in a series of interviews in recent years, report they never received the message.

A fascinating sub-plot of the underwater missile crisis involves U.S. efforts to locate the Soviet submarines. Since 27 September 1962, the U.S. Navy had been tracking the subs using listening posts that detected electronically-compressed "burst radio transmissions" between Soviet Navy command posts and the submarines themselves. The messages could not be deciphered but the location from where they were transmitted could be identified. While U.S. Navy analysts had assumed that the subs were on their way to the Barents Sea for exercises they discovered that they were in the North Atlantic on their way to Cuba. [1] Another high-tech method for tracking subs was the Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS) that detected the noise made by submarine engines. [2] The Navy also used "mad contacts", referring to magnetic anomaly detection (MAD), and "Julie" and "Jezebel" sonobouys. [3]

The Archive's publication also makes available:

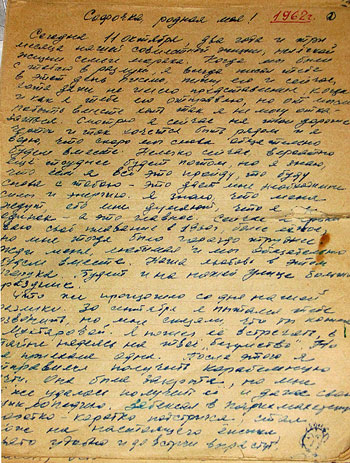

Anatoly Petrovich Andreyev, excerpts of diary entries, October 1962. |

- Photographic images of the evocative diary of submariner Anatoly Petrovich Andreyev, who wrote his account as a letter to his wife describing the equipment breakdowns, the elevated temperatures, the lack of ventilation or fresh water, skin rashes, 30-40% weight loss, and a crew stripped down to their skivvies to deal with the heat.

- Video of Soviet signals intelligence officer Vadim Orlov from the historic 2002 40th anniversary conference on the Missile Crisis, in Havana, Cuba. Orlov served on the B-59 submarine and witnessed how close the sub's commander came to arming the nuclear torpedo aboard.

- Video of Capt. John Peterson (USN retired) at the 2002 Havana conference, describing the hunt for Orlov's submarine, acknowledging that the "signaling depth charges" he and his crew dropped on the Soviets might have sounded very different to the Soviet sailors down below Peterson's destroyer.

Washington, DC, October 27, 2012 – The Cuban Missile Crisis continued long after the "13 days" celebrated by U.S. media, with U.S. armed forces still on DEFCON 2 and Soviet tactical nuclear weapons still in Cuba, according to new documents posted today by the National Security Archive (www.nsarchive.org) from the personal archive of the late Sergo Mikoyan. This is the second installment from the Mikoyan archive donated to the National Security Archive and featured in the new book, The Soviet Cuban Missile Crisis.

These documents, which give one an insight into Soviet thinking and decision making at the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis are supplemented with transcripts of extraordinary interviews with key Soviet political and military figures, all of whom have passed away. These interviews were generously provided to the National Security Archive by our long-time partner, Sherry Jones of Washington Media Associates. Sherry, a five-time Emmy Award winner, conducted these interviews in the summer of 1992 for the groundbreaking documentary "Cuban Missile Crisis: What the World Didn't Know," produced by Sherry Jones for Peter Jennings Reporting, ABC News (Washington Media Associates, 1992). [Jump to the interviews]

On October 28, after Khrushchev and Kennedy had just resolved the most acute and public part of the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Soviet leaders decided to send Anastas Mikoyan to Cuba to settle the crisis between the Soviet Union and their ally, Cuba. Fidel Castro, who was not consulted or even informed about the negotiations between the Soviets and the Americans, sent Khrushchev an angry letter "disagreeing" with the policies of the Soviet government. Khrushchev knew he had a real problem in Cuba-with 42,000 Soviet military personnel armed with tactical nuclear weapons-and an emotional revolutionary leader, who felt betrayed and abandoned by the Kremlin.

Khrushchev's three priorities in regard to Cuba at the moment were: to negotiate a smooth withdrawal of the missiles without provoking the Americans; to get Castro to accept inspections because those were the condition for the American non-invasion pledge; and to keep Cuba as a close ally and thus preserve the Soviet Union's legitimacy in the global communist movement.

Difficult negotiations. Courtesy of Sergo Mikoyan. |

According to Sergo Mikoyan, his father understood his tasks in Cuba to be the following:

First, he had to convince the Cuban leadership that Cuba's security had been assured and that there was no danger of invasion, even though the missiles were being removed.One may add that the seventh major task was to explain the decisions taken by the Kremlin to their own officers and soldiers, who had not been informed by their own government about the negotiations. Those people, who had worked day and night to assemble the missiles and were preparing to fight and die to defend the Cuban revolution against an imperialist aggression, were certainly surprised by the total turnaround by their government, which seemed to be making one concession after another under U.S. pressure.

Second, it was necessary to explain the Kremlin's decisions, which were already announced, and come to an agreement regarding which additional Soviet weapons and military forces could be withdrawn from Cuba with the Cuban leadership's consent, and which should stay on the island.

Third, it was necessary to explain why Khrushchev had agreed to an international ground inspection in Cuba without obtaining Cuba's agreement.

Fourth, it was important to convince the Cuban leaders that this time, in this situation, after such a crisis and such a dangerous moment in international relations, the U.S. President's pledge of non-aggression toward Cuba and his commitment not to allow others to attack Cuba should not be received as yet another empty promise that could be revoked at any moment and under any pretense.

Fifth, it was important to convince Castro to restrain his feelings for some time, even if for a short period, and thus not fire at U.S. surveillance planes.

Sixth, was to return Soviet-Cuban relations as close as possible to their pre-October state.

A lighter moment during the talks. Courtesy of Sergo Mikoyan. |

Mikoyan is also very sensitive to the issue of revolutionary legacy and concerned about the effect of the Soviet withdrawal on Chinese influence in Cuba. He is using every "opportune moment" to criticize the Chinese position and draw comparisons between the Soviet willingness to defend Cuba with the real blood and life of its own soldiers and the Chinese efforts to donate blood by their embassy people in Havana. He suggests that if China was serious about helping Cuba, it could have created a distraction-create a crisis around Taiwan, or take over some Portuguese or British bases, like Hong Kong.

In one of Mikoyan's most eloquent moments during the Cuban trip, he addresses the officers of the Pliev group of forces to explain the decisions of the Soviet government. This is one of the first Soviet efforts to spin the results of the Cuban Missile Crisis to make it look as if Khrushchev has envisioned it to turn out just exactly as it did, that the main goal-the defense of the Cuban revolution-has been achieved. Mikoyan assures them that their task has been carried out brilliantly and that the correlation of forces in the world is changing in the Soviets' favor. In this speech, however, there is some real criticism of the way the Soviet military carried out Operation Anadyr. Mikoyan takes a stab at the rocket forces decision makers (Marshall Biryuzov), describing how the Americans discovered the missiles: "they flew the U-2 and discovered that our missiles were sticking up just like they were at a military parade in Red Square. Only in Red Square they would be placed horizontally, and here they were deployed vertically. Apparently, our rocket forces decided to make an offensive gesture to the Americans."

The Pentagon during the Cuban Missile Crisis

Part I. New Documents

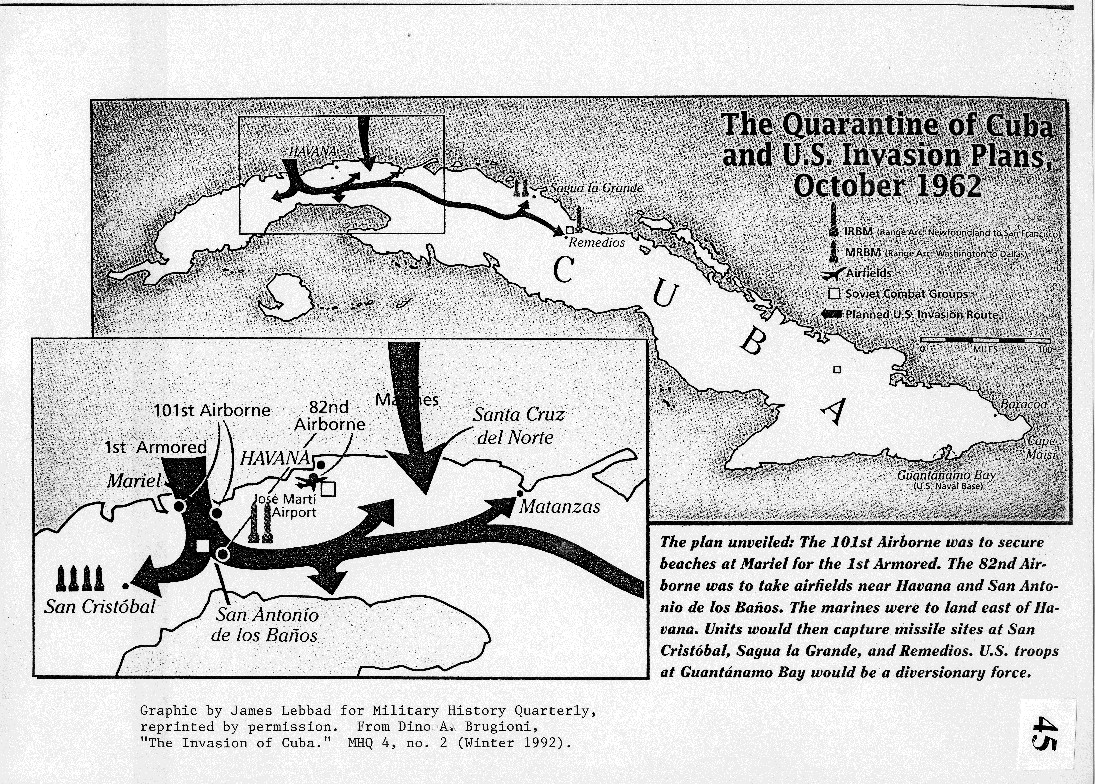

www.nsarchive.org) describe the potentially catastrophic risks of the invasion including 18,500 American casualties in the first 10 days, even without any nuclear explosions.

U.S. intelligence had detected at least one nuclear-capable short-range nuclear weapon launcher (the Luna/Frog) with the Soviet troops in Cuba, so Joint Chiefs chairman Gen. Maxwell Taylor told President Kennedy - in a crucial November 2, 1962 memorandum published here for the first time - that U.S. invasion plans were "adequate and feasible" as long as no battlefield nuclear weapons came into play. If the Cubans were "foolhardy" enough to use nuclear weapons against the invasion, U.S. forces would "respond at once in overwhelming nuclear force against military targets." Taylor cautioned, "If atomic weapons were used, there is no experience factor upon which to base an estimate of casualties. Certainly we might expect to lose very heavily at the outset if caught by surprise, but our retaliation would be rapid and devastating and thus would bring to a sudden close the period of heavy losses."

Taylor's memo came in a tense period when U.S. generals pressed for an invasion, based on their skepticism about the October 28, 1962 announcement by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev that he would withdraw the ballistic missiles in Cuba. Decades later, Soviet evidence would reveal nearly 100 tactical nuclear weapons in Cuba that the U.S. never identified, including cruise missiles 15 miles from the U.S. base at Guantanamo.

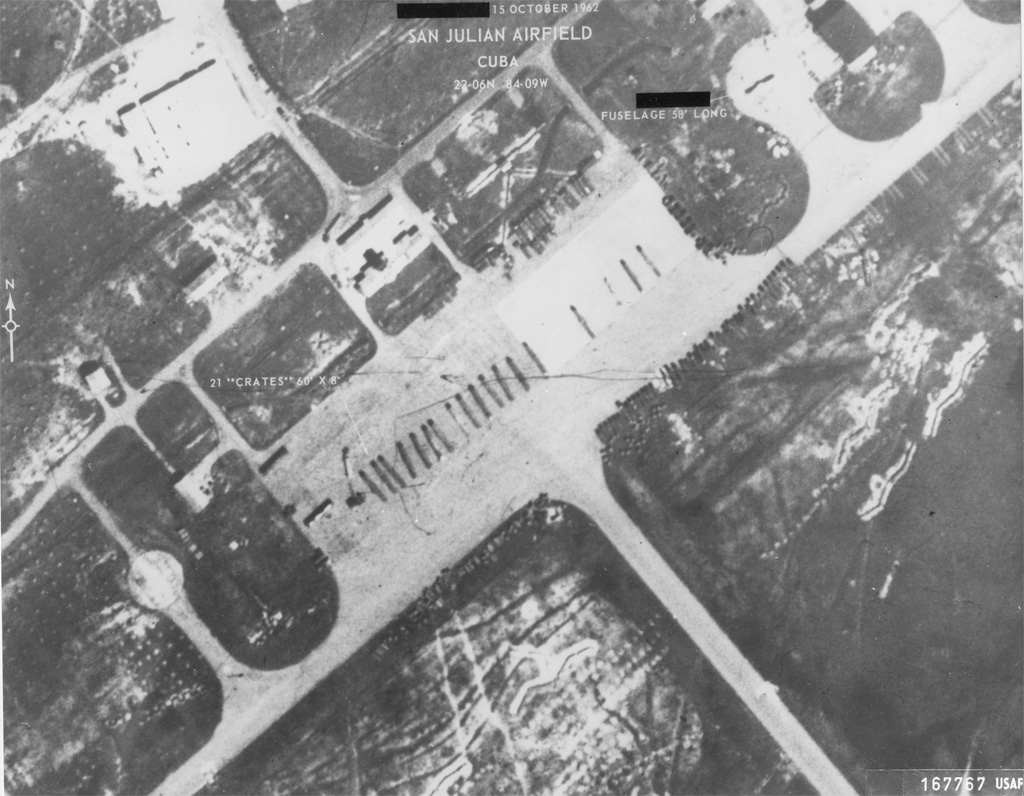

Luckily, U.S. and Soviets capabilities were never put to the horrible test that Taylor described. Many of the "military targets" that Taylor had in mind were located in western Cuba, e.g., IL-28s were at San Julian, so apart from the death and destruction that nuclear detonations would have caused to local populations, prevailing winds (to the northeast) could have brought radioactive fall-out to Havana and further to the Florida coast.

The Taylor memorandum is one item in a compilation of documents focusing on the role of the Pentagon during the missile crisis and drawing upon material recently released by the National Archives, some of it only months ago. A related compilation, "The Pentagon Day-by-Day during the Missile Crisis," including chronologies, personal notes, office calendars and diaries, will be part II of National Security Archive's special collection of Defense Department material. Today's publication shows top level policymakers, including President Kennedy, asking Defense Department officials for information and the latter preparing proposals, plans, and reports to support policymakers in the National Security Council's Executive Committee (ExCom), as they deliberated over how to induce Moscow to withdraw nuclear missiles and bombers from Cuba. The compilation also includes Joint Staff and Air Force contingency plans as well as material prepared by other agencies which surfaced in Pentagon files.

Another item in today's publication provides cost estimates of the missile crisis prepared in response to request made by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. Several months after he asked Pentagon Comptroller, Charles Hitch, for cost figures, Hitch provided a preliminary answer: the missile crisis cost at least 165 million dollars [FY 1963 dollars], with some spending that was still unaccounted. In current FY2013 dollars, adjusting for changes in price levels since 1962, the cost of the missile crisis for the Defense Department was in the range of $1.43 billion.

The Taylor memorandum, the Hitch report and other documents in today's publication are from formerly classified collections of the records of the U.S. Air Force, records of the Secretary of Defense, and the files of Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman General Maxwell Taylor. Documents from these collections shed light on the role of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Staff planners, the Defense Intelligence Agency, and other government agencies in the preparation of contingency plans, strategic readiness measures, and intelligence assessments. Among the disclosures:

- "Deceptive" activities taken by the U.S. military before the crisis to signal to Cuban and Soviet intelligence U.S. "intent either deceptive or real" to take military action. [See Document 40B]

- Air Force Chief of Staff General Curtis LeMay's proposal to General Taylor for actions by the Strategic Air Command, including airborne alert and "maximum readiness posture", which SAC translated into Defcon 2, the readiness level just before nuclear war [See Document 6].

- Proposals to escalate the blockade against Cuba, in the event that negotiations with Moscow over the missile deployments did not work, with measures including expanding the contraband list, changing the location of ship intercepts to a few miles off Cuba, and changing blockade procedures (e.g., forbidding "submerged operations") [See Document 10].

- JCS Chairman Taylor's memo to President Kennedy and Secretary of Defense McNamara on 27 October 1962, hours before a diplomatic settlement was reached, proposing air strikes and an invasion of Cuba [See Document 17].

- "Operation Raincoat"-the code name for air strikes against Soviet missile sites if diplomacy failed [See Document 18].

- "Operation Hot Plate"-- the U.S. Air Force contingency plan to attack the Soviet IL-28 bombers deployed in Cuba in the event that diplomacy failed [See Document 29].

- An Air Force proposal to put Cuban military "installations" on the target list as an option for nuclear attack in the Single Integrated Operational Plan [See Document 36].

- A Defense Intelligence Agency estimate suggesting that Soviet forces in Cuba had a "possible nuclear capability." [See Document 34]

- A series of proposals by the Joint Chiefs and senior Pentagon officials to use the IL-28 crisis as leverage to induce a withdrawal of Soviet forces from Cuba.

Central elements of U.S. government policymaking, diplomatic activities, and military operations during the Missile Crisis are in the public record, including the uniquely important tapes of White House ExCom meetings. For the U.S. side key documents on Missile Crisis diplomacy and high-level policymaking have been published, [2] but some important collections remain classified that may shed light on more of the story. A major State Department collection remains closed at the National Archives as do hundreds of documents in a Secretary of Defense collection, "Sensitive Records on Cuba." The U.S. Air Force's operational files on the missile crisis are also classified (except for a few documents, some of which are included here). Beginning in 2008, the National Security Archive filed declassification requests for Air Force histories of the crisis, but those requests have yet to be fulfilled.

The U.S. Navy's Operational Archive has made important material available [3], but important Navy records have possibly been destroyed (e.g., intelligence summaries) or remain classified, such as "Blue Flag" messages between flag officers during the crisis. In the past, the Defense Intelligence Agency has declassified some documents relating to the missile crisis, but the newly released items in this collection may be the tip of the iceberg. As for National Security Agency operations during the crisis, much remains to be learned, for example, of the intelligence "take" collected by the U.S.S. Oxford stationed off Cuba during and after the crisis. It may take quite a few more Cuban Missile Crisis anniversaries before a fuller record of the events is in the declassified public record.

CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS REVELATIONS: KENNEDY'S SECRET APPROACH TO CASTRO

DECLASSIFIED RFK DOCUMENTS YIELD NEW INFORMATION ON BACK-CHANNEL TO FIDEL CASTRO TO AVOID NUCLEAR WAR

National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 395

Posted - October 12, 2012

Edited by Peter Kornbluh

For more information contact:

Peter Kornbluh - 202/374-7281 or peter.kornbluh@gmail.com

Washington, DC, October 12, 2012 – On the 50th

anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis, new documents from the Robert Kennedy

papers declassified

yesterday and posted today by the National Security Archive reveal

previously unknown details of the Kennedy administration's secret effort to find

an accord with Cuba that would remove the Soviet missiles in return for a modus

vivendi between Washington and Havana.

The 2700 pages of RFK papers opened yesterday include the first proposed letter to "Mr. F.C.," evaluated by the Executive Committee of advisors to Kennedy on October 17th--just one day after the president learned of the existence of the Soviet missiles in Cuba. The draft letter, available to historians for the first time, initiated a chain of events that led to a complicated back-channel diplomacy between Washington and Havana at the height of what Kennedy aide Arthur Schlesinger called "the most dangerous moment in human history."

The Archive's Cuba analyst, Peter Kornbluh, who was the first person to review the RFK papers at the Kennedy Library, noted that the documents "reinforce the key historical lesson of the missile crisis: the need and role for creative diplomacy to avoid the threat of nuclear Armageddon." Kornbluh noted that the State Department's own official historians, referring to the initial letter to Castro, had admitted that "none of these drafts have been found." The fact that the Robert Kennedy papers have yielded new information previously undiscovered by the government's own researchers, Kornbluh said, "underscores the historical importance of this declassification on the 50th anniversary of the crisis."

The Archive also posted two diagrams Robert Kennedy drew on his notepad during the crisis deliberations, including his initial tally of the "hawks" and the "doves" as Kennedy's advisors took positions on diplomacy vs. the use of force against Cuba.

The draft letter warned Castro that by deploying the ballistic missiles the Soviets had "raised grave issues for Cuba. To serve their interests they have justified the Western Hemisphere countries in making an attack on Cuba which would lead to the immediate overthrow of your regime." Moreover, according to this proposed communication, Nikita Khrushchev was quietly hinting that he would betray Cuba by trading concessions on Berlin for "Soviet abandonment of Cuba." Warning that failure to remove the missiles would lead to U.S. "measures of vital significance for the future of Cuba," the message offered an oblique carrot of negotiations for better relations once the Soviets and their weapons of mass destruction were gone.

During the early deliberations of how to respond to the missiles in Cuba Kennedy's top advisors pressed him to reject this message to Cuba because it would undermine the option of a surprise U.S. air attack on the island. After Kennedy decided on an interim option of a naval quarantine of Cuba to buy time for diplomacy to convince the Soviets to withdraw the missiles, he ordered the State Department to come up with diplomatic alternatives to attacking Cuba.

In an October 25 memorandum, titled "Political Path," the State Department submitted a series of creative options for resolving the crisis peacefully, including allowing the United Nations to take control of both the Soviet missile bases in Cuba and the U.S. missile bases in Turkey. The document also provided an outline for an "approach to Castro" through Brazil, with a message to Castro underscoring his options: "the overthrow of his regime, if not its physical destruction," or "assurances, regardless of whether we intended to carry them out, that we would not ourselves undertake to overthrow the regime" if he expelled both the missiles and the Russians.

During an Excomm meeting on October 26, Kennedy actually approved a version of this message to be sent to Castro, albeit disguised as a Brazilian peace initiative sent by the government of populist president Joao Goulart, rather than one from Washington. The draft cable, published here for the first time, instructed the Brazilians to secretly carry the message to Castro that his regime and the "well-being of the Cuban people" were in "great jeopardy" if he didn't expel the Russians and their weapons. If he did, however, "many changes in the relations between Cuba and the OAS countries, including the U.S., could flow."

By the time the Brazilian emissary arrived in Havana on October 29th, however, the urgency and relevance of Kennedy's Brazilian back-channel message had been eclipsed by events. On October 28, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev agreed to withdraw the missiles--in return for a Kennedy's public pledge not to invade Cuba, and the President's secret promise to withdraw U.S. missiles from Turkey sometime in the near future.

For more than 40 years, the details of Kennedy's approach to Castro remained Top Secret. In 2004, based on declassified documents found in the archives of the Brazilian foreign ministry and the Excomm tapes, George Washington University historian James Hershberg published the first comprehensive account of the furtive diplomatic initiative in the Journal of Cold War Studies (Part 1, Part 2). An abbreviated account of the Castro approach, written by Peter Kornbluh, appears in the November 2012 issue of Cigar Aficionado. The story is also recounted in Kornbluh's forthcoming book (with William LeoGrande), Talking with Castro: The Untold History of Dialogue between the United States and Cuba.

The 2700 pages of RFK papers opened yesterday include the first proposed letter to "Mr. F.C.," evaluated by the Executive Committee of advisors to Kennedy on October 17th--just one day after the president learned of the existence of the Soviet missiles in Cuba. The draft letter, available to historians for the first time, initiated a chain of events that led to a complicated back-channel diplomacy between Washington and Havana at the height of what Kennedy aide Arthur Schlesinger called "the most dangerous moment in human history."

The Archive's Cuba analyst, Peter Kornbluh, who was the first person to review the RFK papers at the Kennedy Library, noted that the documents "reinforce the key historical lesson of the missile crisis: the need and role for creative diplomacy to avoid the threat of nuclear Armageddon." Kornbluh noted that the State Department's own official historians, referring to the initial letter to Castro, had admitted that "none of these drafts have been found." The fact that the Robert Kennedy papers have yielded new information previously undiscovered by the government's own researchers, Kornbluh said, "underscores the historical importance of this declassification on the 50th anniversary of the crisis."

The Archive also posted two diagrams Robert Kennedy drew on his notepad during the crisis deliberations, including his initial tally of the "hawks" and the "doves" as Kennedy's advisors took positions on diplomacy vs. the use of force against Cuba.

The draft letter warned Castro that by deploying the ballistic missiles the Soviets had "raised grave issues for Cuba. To serve their interests they have justified the Western Hemisphere countries in making an attack on Cuba which would lead to the immediate overthrow of your regime." Moreover, according to this proposed communication, Nikita Khrushchev was quietly hinting that he would betray Cuba by trading concessions on Berlin for "Soviet abandonment of Cuba." Warning that failure to remove the missiles would lead to U.S. "measures of vital significance for the future of Cuba," the message offered an oblique carrot of negotiations for better relations once the Soviets and their weapons of mass destruction were gone.

During the early deliberations of how to respond to the missiles in Cuba Kennedy's top advisors pressed him to reject this message to Cuba because it would undermine the option of a surprise U.S. air attack on the island. After Kennedy decided on an interim option of a naval quarantine of Cuba to buy time for diplomacy to convince the Soviets to withdraw the missiles, he ordered the State Department to come up with diplomatic alternatives to attacking Cuba.

In an October 25 memorandum, titled "Political Path," the State Department submitted a series of creative options for resolving the crisis peacefully, including allowing the United Nations to take control of both the Soviet missile bases in Cuba and the U.S. missile bases in Turkey. The document also provided an outline for an "approach to Castro" through Brazil, with a message to Castro underscoring his options: "the overthrow of his regime, if not its physical destruction," or "assurances, regardless of whether we intended to carry them out, that we would not ourselves undertake to overthrow the regime" if he expelled both the missiles and the Russians.

During an Excomm meeting on October 26, Kennedy actually approved a version of this message to be sent to Castro, albeit disguised as a Brazilian peace initiative sent by the government of populist president Joao Goulart, rather than one from Washington. The draft cable, published here for the first time, instructed the Brazilians to secretly carry the message to Castro that his regime and the "well-being of the Cuban people" were in "great jeopardy" if he didn't expel the Russians and their weapons. If he did, however, "many changes in the relations between Cuba and the OAS countries, including the U.S., could flow."

By the time the Brazilian emissary arrived in Havana on October 29th, however, the urgency and relevance of Kennedy's Brazilian back-channel message had been eclipsed by events. On October 28, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev agreed to withdraw the missiles--in return for a Kennedy's public pledge not to invade Cuba, and the President's secret promise to withdraw U.S. missiles from Turkey sometime in the near future.

For more than 40 years, the details of Kennedy's approach to Castro remained Top Secret. In 2004, based on declassified documents found in the archives of the Brazilian foreign ministry and the Excomm tapes, George Washington University historian James Hershberg published the first comprehensive account of the furtive diplomatic initiative in the Journal of Cold War Studies (Part 1, Part 2). An abbreviated account of the Castro approach, written by Peter Kornbluh, appears in the November 2012 issue of Cigar Aficionado. The story is also recounted in Kornbluh's forthcoming book (with William LeoGrande), Talking with Castro: The Untold History of Dialogue between the United States and Cuba.